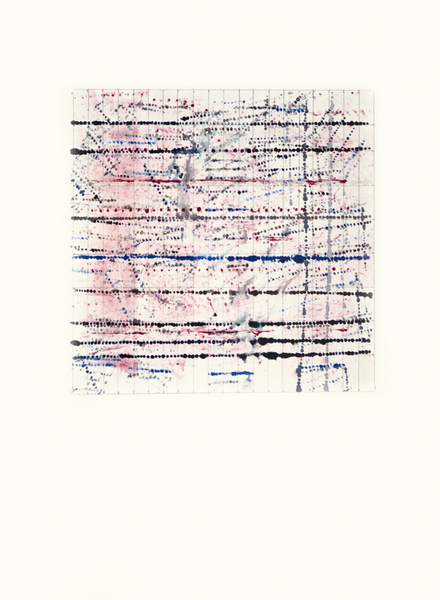

Keeping Score

Series of four monotypes, 2013

11 x 15 Daniel Smith Lenox paper

Image size 10 x 10 inches

#1 “Notation”

#2 “Pulse”

#3 “Color of Sound”

#4 “Shape Notes

Subvert, Dance, Slide, Skate, Break Down

Hmm. It may well seem to the reader that I take intellectual intention with me into the studio. But I can’t. I’ve tried it, and it’s a bust.

Intention and ego are quickly disposed of (the big trash bin is just outside the door) because the basic tools of the studio — plexiglass, ink, brayers, chemicals, mechanical etching press — are at hand and used in the hand, and the hand, as far as I’m concerned, is connected to the heart. A direct line: life support.

But I do think about things, about where they come from, about what’s underneath them, about what I can’t easily perceive. And I’m connecting these very things into a thin tissue now, two years after making the four pieces of Keeping Score.

I’m not sure why exactly in early 2013 I began thinking intensely about Agnes Martin’s work. I mean, she’s been with me since I first really looked at her work. This was at Dia:Beacon the day it opened, in 2003. But I bought Arne Glimcher’s Agnes Martin: Paintings, Writings, Remembrances (2012) and was delighted to find Martin’s own writing in it — almost literally. She used old-fashioned six-by-nine lined notebook paper, and clutches of her handwritten words are reproduced and tipped in to the binding of this very big book. (Glimcher was Martin’s longtime gallerist.)

The reproductions of her visual work, from the 1950s until she died, at ninety-two, in 2005, are exquisite, and for a few months Martin’s writing and her paintings became a morning devotional. I looked and read on the couch in the living room, cup of tea by my side.

Her point of view remained clear and consistent throughout the years. She was steadfast in her belief of what an artist must do: set aside the ego and excise anything in the life that was extraneous to the work. To wit:

It seems as tho all the things of any worth do not apply to art work — strength, ability, knowledge, intelligence, determination, earnestness, striving, overcoming. Since it is something received, all of that is unnecessary.

What she meant by “something received” is the notion of what she called “inspiration.” She referred to it again and again in her own writing and in interviews. Inspiration could come only in the letting go of most of the things of this world, which in her case meant relationships with other people and, ultimately, interests in other deeply involving pastimes, such as gardening and food. (As she worked on a series of paintings in her studio in New Mexico, she consumed only bananas and, I think, coffee, for weeks.)

By “inspiration,” she meant what other people have called the gift, the state of being that comes to an artist of any kind when she does indeed try to excise the ego and then patiently wait. In Soto Zen Buddhism, Shunryu Suzuki referred to this as the “beginner’s mind.” It’s the energy that comes, unbidden,, if one prepares one’s life to receive it. (Martin, evidentially, studied Zen Buddhism, though she doesn’t mention it in her writing.)

It’s the mind I like to have in my own studio, though I think of it in the way my own little child would think “What will happen if I stick my carrot into the light socket?”

But still, I do think and read and wonder about things, and these things become a sort of wallpaper in my mind.

In the 1960s, Martin began to use in her art the grid as the geometric organizing principle. She then took a hiatus from painting for eight years, and in 1973 returned to it. Glimcher writes that the grids that appeared in this reactivated work “constitute the grammar of linear divisions that she would employ for the rest of her life.”

The grid is one way we human beings make sense of space. It’s a way of mapping our world. The standard printing paper for my etching press, used for making monotypes, is twenty-two by thirty inches. I often work in half-sheets (as I did with the series Keeping Score), which are eleven by fifteen. So there’s always this rectangular real estate.

Early on, I gravitated to the square (mapping and containing — that’s how I think of the square. Comforting). I’m particularly fond of the ten-inch plexiglass square used on the half-sheet. I worked for a few years on the square within the square within the square within the square in a very controlled way. But I was just beginning to understand about the properties of plexiglass and ink . . .

I suppose grids had been elbowing their way into the wallpaper of my mind when I made the first monotype of this series (but here labeled #4), in which the grid is roughly drawn on a ten-by-ten piece of plexi that had been inked up with an ivory color. I used a very simple wood stylus for this (so simple that it was a plain, sharpened stick, the kind used for manicures!). Then I used the stylus to dot on some ink. Dot, dot, dot.

But it was too static (I think that was my reaction). Then I sent a two-inch brayer over it.

Hmm. What would happen if I drew a grid on the paper first? (This all unfolded over some weeks.) And then prepared the plate . . .

Grids invite ideas of standardization, engineering, city planning. But Martin’s grids, or many of them, aren’t rigidly organized. Or at least there’s freedom within the organization. Parts of them shape-change and/or skip spaces. It’s as if they’re a release from inflexibility. When I began drawing these grids on printing paper, I saw Martin’s in a way — believe me — I hadn’t up to then.

So now I had a square within a rectangle and a grid within the square, and in some grids rectangles with the square . . .

But that’s not at all what these prints in Keeping Score are about.

To be sure, I loved the physicality of drawing with a soft pencil into the softish printing paper. Using a straightedge. Sharpening the pencil more than once. Keeping the paper neat and clean.

But I “knew,” on a gut level, that the grid wouldn’t work for me unless I could subvert it, dance over it, slide over it, skate over it, break it down.

This is what I love about monotype — when it seems to arrive at a particular point and is solely in the moment. If I’m there with it in the same spirit, I have no idea what will happen. There may be too much ink or not enough, or the ink might be too thin. The plate may slip on the press. Perhaps the paper won’t be straight on the press bed (a recurring problem). Maybe I’ll make a big muddy mess.

But I make a move on the plate. (What else is there to do?) And another one. The plate is arranged, ink-side up, on the press bed. Paper is gently arranged on top of the plate. The felt blankets of the press are laid on top. Then I turn the big wheel.

And this is, more or less, how graphite and ink managed to get onto some paper.

I don’t know how many prints I made in the series, or when I first “saw” that the prints were about sound. But as I went along, I began to apprehend, to sense, to hear the rhythm in the prints — perhaps I hear inner music. But I had no idea, and no intent, of sound. To “see” this was a surprise. A gift.

Notation / #1 Keeping Score

Pulse / #2 Keeping Score

Color of Sound / #3 Keeping Score

Shape Notes / #4 Keeping Score